Learn about Linkers

Whether your interested in low-level development or reverse engineering malware, understanding how linkers work and being able to write your own linker script is an important skill.

I recently created a gitbook, that will elaborate on several important linker topics, such as: PLT/GOT, Relocation, Dynamic Linking, linking with shared libraries, loaders, and ELF binaries.

I’ve also included some additional resources for those interested in learning more.

Gitbook Knowledge Base - Linkers

Check out my Gitbook and feel free to contact me with any questions, corrections, or connections.

Why Learn About Linkers?

Learning to write a linker script is vital when developing an operating system or hypervisor. Usually, user-space development will include linker scripts with the toolchain; however, these are unsuitable when writing a kernel.

When writing a kernel, we must write our own linker to link the bootloader and kernel object files together to produce a kernel image. Admittedly, writing a linker is not a skill that many possess; nevertheless, it is vital when developing a kernel or hypervisor.

The GNU Linker (ld) and Linker Script are well-documented and include more information than you probably need. I will do my best to synthesize this to include the most important parts. If you’re interested in a comprehensive study, here are a few helpful resources.

Additional Resources

Linkers and Loaders (Levine): This book is old, but it is gold! Look no further to learn about linkers and loaders.

Advanced Compiler Design (Muchnick): This is the gold standard for learning about compilers and includes a lot of good information on linkers. You’ll learn about PLT and GOT, the Procedure Linkage Table, and the Global Offset Table, which are crucial for understanding dynamic linking and reverse engineering.

Blog Series (Ian Lance Tayler): Ian is the developer of GOLD, which is a linker for ELF binaries and is also included in GNU binutils. He knows his stuff!

What is a Linker?

Linkers are an important part of a development toolchain used by any low-level programmer. Other important components include the compiler and assembler.

In a future post, I’ll discuss toolchains and cross-compilers, which are important when you need to target an architecture that differs from the local computer. My computers have Intel, M2, and AMD/NVIDIA(GPU) architectures, and I will target a RISC-V architecture.

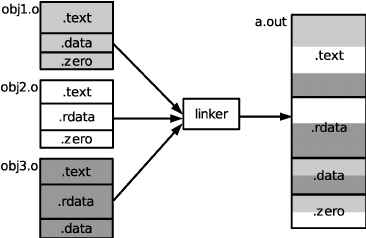

Most developers include GNU binutils in their toolchain, which includes ld, the GNU linker. To understand linkers, you must first understand why they are needed. Compilers generate object files for each source code file that contain information about that source file. The object file information, however, is incomplete; most source files reference other source files to include part of the code. Source files from other programs can also be referenced to include portions of the program code in the current program.

The linker is responsible for combining all of these object files into a single object file or binary. It is also responsible for reorganizing memory so that the combined pieces fit together; this is done by combining similar sections. Finally, the linker must modify the addresses to allow the program to run under the new memory organization.

Object Files

In my Gitbook, I included an example from a cryptographic program that I wrote, implementing Diffie-Hellman and RSA. Here, I’ll include a simple picture that illustrates the point.

Types of Linking

Linkers can link statically or dynamically. Static linking implies references are fully resolved before runtime. Dynamic linking means that the location where the library will be loaded isn’t known until runtime; instead, the references are resolved during runtime, dynamically.

When the compiler’s assembler runs, it doesn’t know the address of external references so it marks places a zero in the object file. This is the incomplete information that I alluded to in the previous section. The linker is responsible for solving this reference, and it does so either dynamically or statically. In most cases, references to shared libraries are solved dynamically during runtime. The linker builds a jump table and a dynamic loader is used to fill the table.

I will include additional notes that explore linkers and loaders more in depth.

Analyzing Linker Script

On Linux, run ld --verbose to view the default linker script used by your system. I will give a brief introduction to the linker script, covering only the main parts. If you’re interested in learning more, checkout some of the resources listed above.

GNU Linker Script

OUTPUT_FORMAT("elf64-x86-64", "elf64-x86-64",

"elf64-x86-64")

OUTPUT_ARCH(i386:x86-64)

ENTRY(_start)

SEARCH_DIR("/usr/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/lib64"); SEARCH_DIR("/usr/lib"); SEARCH_DIR("/usr/local/lib"); SEARCH_DIR("/usr/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/lib");

SECTIONS

{

PROVIDE (__executable_start = SEGMENT_START("text-segment", 0x400000)); . = SEGMENT_START("text-segment", 0x400000) + SIZEOF_HEADERS;

.interp : { *(.interp) }

.note.gnu.build-id : { *(.note.gnu.build-id) }

.hash : { *(.hash) }

.gnu.hash : { *(.gnu.hash) }

.dynsym : { *(.dynsym) }

.dynstr : { *(.dynstr) }

.gnu.version : { *(.gnu.version) }

.gnu.version_d : { *(.gnu.version_d) }

.gnu.version_r : { *(.gnu.version_r) }

.rela.dyn :

{

*(.rela.init)

*(.rela.text .rela.text.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.t.*)

*(.rela.fini)

*(.rela.rodata .rela.rodata.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.r.*)

*(.rela.data .rela.data.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.d.*)

*(.rela.tdata .rela.tdata.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.td.*)

*(.rela.tbss .rela.tbss.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.tb.*)

*(.rela.ctors)

*(.rela.dtors)

*(.rela.got)

*(.rela.bss .rela.bss.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.b.*)

*(.rela.ldata .rela.ldata.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.l.*)

*(.rela.lbss .rela.lbss.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.lb.*)

*(.rela.lrodata .rela.lrodata.* .rela.gnu.linkonce.lr.*)

*(.rela.ifunc)

}

.rela.plt :

{

*(.rela.plt)

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__rela_iplt_start = .);

*(.rela.iplt)

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__rela_iplt_end = .);

}

.relr.dyn : { *(.relr.dyn) }

. = ALIGN(CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE));

.init :

{

KEEP (*(SORT_NONE(.init)))

}

.plt : { *(.plt) *(.iplt) }

.plt.got : { *(.plt.got) }

.plt.sec : { *(.plt.sec) }

.text :

{

*(.text.unlikely .text.*_unlikely .text.unlikely.*)

*(.text.exit .text.exit.*)

*(.text.startup .text.startup.*)

*(.text.hot .text.hot.*)

*(SORT(.text.sorted.*))

*(.text .stub .text.* .gnu.linkonce.t.*)

/* .gnu.warning sections are handled specially by elf.em. */

*(.gnu.warning)

}

.fini :

{

KEEP (*(SORT_NONE(.fini)))

}

PROVIDE (__etext = .);

PROVIDE (_etext = .);

PROVIDE (etext = .);

. = ALIGN(CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE));

/* Adjust the address for the rodata segment. We want to adjust up to

the same address within the page on the next page up. */

. = SEGMENT_START("rodata-segment", ALIGN(CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE)) + (. & (CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE) - 1)));

.rodata : { *(.rodata .rodata.* .gnu.linkonce.r.*) }

.rodata1 : { *(.rodata1) }

.eh_frame_hdr : { *(.eh_frame_hdr) *(.eh_frame_entry .eh_frame_entry.*) }

.eh_frame : ONLY_IF_RO { KEEP (*(.eh_frame)) *(.eh_frame.*) }

.sframe : ONLY_IF_RO { *(.sframe) *(.sframe.*) }

.gcc_except_table : ONLY_IF_RO { *(.gcc_except_table .gcc_except_table.*) }

.gnu_extab : ONLY_IF_RO { *(.gnu_extab*) }

/* These sections are generated by the Sun/Oracle C++ compiler. */

.exception_ranges : ONLY_IF_RO { *(.exception_ranges*) }

/* Adjust the address for the data segment. We want to adjust up to

the same address within the page on the next page up. */

. = DATA_SEGMENT_ALIGN (CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE), CONSTANT (COMMONPAGESIZE));

/* Exception handling */

.eh_frame : ONLY_IF_RW { KEEP (*(.eh_frame)) *(.eh_frame.*) }

.sframe : ONLY_IF_RW { *(.sframe) *(.sframe.*) }

.gnu_extab : ONLY_IF_RW { *(.gnu_extab) }

.gcc_except_table : ONLY_IF_RW { *(.gcc_except_table .gcc_except_table.*) }

.exception_ranges : ONLY_IF_RW { *(.exception_ranges*) }

/* Thread Local Storage sections */

.tdata :

{

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__tdata_start = .);

*(.tdata .tdata.* .gnu.linkonce.td.*)

}

.tbss : { *(.tbss .tbss.* .gnu.linkonce.tb.*) *(.tcommon) }

.preinit_array :

{

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__preinit_array_start = .);

KEEP (*(.preinit_array))

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__preinit_array_end = .);

}

.init_array :

{

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__init_array_start = .);

KEEP (*(SORT_BY_INIT_PRIORITY(.init_array.*) SORT_BY_INIT_PRIORITY(.ctors.*)))

KEEP (*(.init_array EXCLUDE_FILE (*crtbegin.o *crtbegin?.o *crtend.o *crtend?.o ) .ctors))

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__init_array_end = .);

}

.fini_array :

{

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__fini_array_start = .);

KEEP (*(SORT_BY_INIT_PRIORITY(.fini_array.*) SORT_BY_INIT_PRIORITY(.dtors.*)))

KEEP (*(.fini_array EXCLUDE_FILE (*crtbegin.o *crtbegin?.o *crtend.o *crtend?.o ) .dtors))

PROVIDE_HIDDEN (__fini_array_end = .);

}

.ctors :

{

/* gcc uses crtbegin.o to find the start of

the constructors, so we make sure it is

first. Because this is a wildcard, it

doesn't matter if the user does not

actually link against crtbegin.o; the

linker won't look for a file to match a

wildcard. The wildcard also means that it

doesn't matter which directory crtbegin.o

is in. */

KEEP (*crtbegin.o(.ctors))

KEEP (*crtbegin?.o(.ctors))

/* We don't want to include the .ctor section from

the crtend.o file until after the sorted ctors.

The .ctor section from the crtend file contains the

end of ctors marker and it must be last */

KEEP (*(EXCLUDE_FILE (*crtend.o *crtend?.o ) .ctors))

KEEP (*(SORT(.ctors.*)))

KEEP (*(.ctors))

}

.dtors :

{

KEEP (*crtbegin.o(.dtors))

KEEP (*crtbegin?.o(.dtors))

KEEP (*(EXCLUDE_FILE (*crtend.o *crtend?.o ) .dtors))

KEEP (*(SORT(.dtors.*)))

KEEP (*(.dtors))

}

.jcr : { KEEP (*(.jcr)) }

.data.rel.ro : { *(.data.rel.ro.local* .gnu.linkonce.d.rel.ro.local.*) *(.data.rel.ro .data.rel.ro.* .gnu.linkonce.d.rel.ro.*) }

.dynamic : { *(.dynamic) }

.got : { *(.got) *(.igot) }

. = DATA_SEGMENT_RELRO_END (SIZEOF (.got.plt) >= 24 ? 24 : 0, .);

.got.plt : { *(.got.plt) *(.igot.plt) }

.data :

{

*(.data .data.* .gnu.linkonce.d.*)

SORT(CONSTRUCTORS)

}

.data1 : { *(.data1) }

_edata = .; PROVIDE (edata = .);

. = ALIGN(ALIGNOF(NEXT_SECTION));

__bss_start = .;

.bss :

{

*(.dynbss)

*(.bss .bss.* .gnu.linkonce.b.*)

*(COMMON)

/* Align here to ensure that the .bss section occupies space up to

_end. Align after .bss to ensure correct alignment even if the

.bss section disappears because there are no input sections.

FIXME: Why do we need it? When there is no .bss section, we do not

pad the .data section. */

. = ALIGN(. != 0 ? 64 / 8 : 1);

}

.lbss :

{

*(.dynlbss)

*(.lbss .lbss.* .gnu.linkonce.lb.*)

*(LARGE_COMMON)

}

. = ALIGN(64 / 8);

. = SEGMENT_START("ldata-segment", .);

.lrodata ALIGN(CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE)) + (. & (CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE) - 1)) :

{

*(.lrodata .lrodata.* .gnu.linkonce.lr.*)

}

.ldata ALIGN(CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE)) + (. & (CONSTANT (MAXPAGESIZE) - 1)) :

{

*(.ldata .ldata.* .gnu.linkonce.l.*)

. = ALIGN(. != 0 ? 64 / 8 : 1);

}

. = ALIGN(64 / 8);

_end = .; PROVIDE (end = .);

. = DATA_SEGMENT_END (.);

/* Stabs debugging sections. */

.stab 0 : { *(.stab) }

.stabstr 0 : { *(.stabstr) }

.stab.excl 0 : { *(.stab.excl) }

.stab.exclstr 0 : { *(.stab.exclstr) }

.stab.index 0 : { *(.stab.index) }

.stab.indexstr 0 : { *(.stab.indexstr) }

.comment 0 (INFO) : { *(.comment); LINKER_VERSION; }

.gnu.build.attributes : { *(.gnu.build.attributes .gnu.build.attributes.*) }

/* DWARF debug sections.

Symbols in the DWARF debugging sections are relative to the beginning

of the section so we begin them at 0. */

/* DWARF 1. */

.debug 0 : { *(.debug) }

.line 0 : { *(.line) }

/* GNU DWARF 1 extensions. */

.debug_srcinfo 0 : { *(.debug_srcinfo) }

.debug_sfnames 0 : { *(.debug_sfnames) }

/* DWARF 1.1 and DWARF 2. */

.debug_aranges 0 : { *(.debug_aranges) }

.debug_pubnames 0 : { *(.debug_pubnames) }

/* DWARF 2. */

.debug_info 0 : { *(.debug_info .gnu.linkonce.wi.*) }

.debug_abbrev 0 : { *(.debug_abbrev) }

.debug_line 0 : { *(.debug_line .debug_line.* .debug_line_end) }

.debug_frame 0 : { *(.debug_frame) }

.debug_str 0 : { *(.debug_str) }

.debug_loc 0 : { *(.debug_loc) }

.debug_macinfo 0 : { *(.debug_macinfo) }

/* SGI/MIPS DWARF 2 extensions. */

.debug_weaknames 0 : { *(.debug_weaknames) }

.debug_funcnames 0 : { *(.debug_funcnames) }

.debug_typenames 0 : { *(.debug_typenames) }

.debug_varnames 0 : { *(.debug_varnames) }

/* DWARF 3. */

.debug_pubtypes 0 : { *(.debug_pubtypes) }

.debug_ranges 0 : { *(.debug_ranges) }

/* DWARF 5. */

.debug_addr 0 : { *(.debug_addr) }

.debug_line_str 0 : { *(.debug_line_str) }

.debug_loclists 0 : { *(.debug_loclists) }

.debug_macro 0 : { *(.debug_macro) }

.debug_names 0 : { *(.debug_names) }

.debug_rnglists 0 : { *(.debug_rnglists) }

.debug_str_offsets 0 : { *(.debug_str_offsets) }

.debug_sup 0 : { *(.debug_sup) }

.gnu.attributes 0 : { KEEP (*(.gnu.attributes)) }

/DISCARD/ : { *(.note.GNU-stack) *(.gnu_debuglink) *(.gnu.lto_*) }

}

GNU Linker Script Explanation

OUTPUT_FORMAT(): This declarative allows you to provide an output format for your executable. For a listing of acceptable formats, runobjdump -i.ENTRY(): ENRTRY allows you to include the symbol defined in your program in the .text section that represents the first byte of executable code; that is, the entrypoint. Checkout the disassembled example below, which shows the start entrypoint. Note: In the disassembled code, the program (that only prints) was written in C and then compiled. The start section includes a lot of extra work to prepare the program, such as initializing registers, getting command-line arguments, calling main(), and handling exit().SECTIONS(): This allows you to define a structured format in the output (object) file by segmenting the data in memory. The linker script allows the developer to control the type of data that is in each section. To learn about ELF binaries and the included sections, visit the Linux manual page.- Declaring a section follows the format .section and sections are interpreted in the order they are listed. For example, .text is the section in ELF binaries that includes the executable code of your program.

- You can also map subsection names using a wildcard, to a specific object file or any object file. For example, (.text.unlikely .text._unlikely .text.unlikely.*) will match any section that matches the pattern. Notice the wildcard before the parenthesis; alternatively, we could specify the object file like startup.o(.text.unlikely …) however the wildcard is more common because file names can change. Why are there so many alias names? It allows the developer to organize the code by controlling where it is placed in memory. In the example above, sections matching the that text pattern is unlikely to be executed. Grouping that code together can, for example, improve cache locality by letter hot code (code that is frequently executed) be grouped together.

PROVIDE(): provides a symbol that can be referenced code.

MEMORY(): The memory declaration is not included in the example above; however, it is very important for kernel developers. The example below, shows how a memory region is declared with access attributes. Sections defined in SECTIONS can map to a specific region by adding the following after the closing bracket: >RAM AT>ROM. The first ( >RAM ) means store the preceding section in RAM and ( AT>ROM ) sets the LMA (load memory address) to ROM, or read-only memory.

Code Examples

Memory Declarative

MEMORY

{

ROM (rx) : ORIGIN = 0, LENGTH = 256k

RAM (wx) : org = 0x00100000, len = 1M

}

Disassembled Example (Objdump output)

output: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .init:

0000000000001000 <_init>:

1000: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1004: 48 83 ec 08 sub rsp,0x8

1008: 48 8b 05 c1 2f 00 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2fc1] # 3fd0 <__gmon_start__@Base>

100f: 48 85 c0 test rax,rax

1012: 74 02 je 1016 <_init+0x16>

1014: ff d0 call rax

1016: 48 83 c4 08 add rsp,0x8

101a: c3 ret

Disassembly of section .plt:

0000000000001020 <puts@plt-0x10>:

1020: ff 35 ca 2f 00 00 push QWORD PTR [rip+0x2fca] # 3ff0 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x8>

1026: ff 25 cc 2f 00 00 jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x2fcc] # 3ff8 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x10>

102c: 0f 1f 40 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

0000000000001030 <puts@plt>:

1030: ff 25 ca 2f 00 00 jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x2fca] # 4000 <puts@GLIBC_2.2.5>

1036: 68 00 00 00 00 push 0x0

103b: e9 e0 ff ff ff jmp 1020 <_init+0x20>

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000001040 <main>:

1040: 48 83 ec 08 sub rsp,0x8

1044: 48 8d 3d b9 0f 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0xfb9] # 2004 <_IO_stdin_used+0x4>

104b: e8 e0 ff ff ff call 1030 <puts@plt>

1050: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

1052: 48 83 c4 08 add rsp,0x8

1056: c3 ret

1057: 66 0f 1f 84 00 00 00 nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

105e: 00 00

0000000000001060 <_start>:

1060: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1064: 31 ed xor ebp,ebp

1066: 49 89 d1 mov r9,rdx

1069: 5e pop rsi

106a: 48 89 e2 mov rdx,rsp

106d: 48 83 e4 f0 and rsp,0xfffffffffffffff0

1071: 50 push rax

1072: 54 push rsp

1073: 45 31 c0 xor r8d,r8d

1076: 31 c9 xor ecx,ecx

1078: 48 8d 3d c1 ff ff ff lea rdi,[rip+0xffffffffffffffc1] # 1040 <main>

107f: ff 15 3b 2f 00 00 call QWORD PTR [rip+0x2f3b] # 3fc0 <__libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.34>

1085: f4 hlt

1086: 66 2e 0f 1f 84 00 00 cs nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

108d: 00 00 00

1090: 48 8d 3d 81 2f 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0x2f81] # 4018 <__TMC_END__>

1097: 48 8d 05 7a 2f 00 00 lea rax,[rip+0x2f7a] # 4018 <__TMC_END__>

109e: 48 39 f8 cmp rax,rdi

10a1: 74 15 je 10b8 <_start+0x58>

10a3: 48 8b 05 1e 2f 00 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2f1e] # 3fc8 <_ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable@Base>

10aa: 48 85 c0 test rax,rax

10ad: 74 09 je 10b8 <_start+0x58>

10af: ff e0 jmp rax

10b1: 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

10b8: c3 ret

10b9: 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

10c0: 48 8d 3d 51 2f 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0x2f51] # 4018 <__TMC_END__>

10c7: 48 8d 35 4a 2f 00 00 lea rsi,[rip+0x2f4a] # 4018 <__TMC_END__>

10ce: 48 29 fe sub rsi,rdi

10d1: 48 89 f0 mov rax,rsi

10d4: 48 c1 ee 3f shr rsi,0x3f

10d8: 48 c1 f8 03 sar rax,0x3

10dc: 48 01 c6 add rsi,rax

10df: 48 d1 fe sar rsi,1

10e2: 74 14 je 10f8 <_start+0x98>

10e4: 48 8b 05 ed 2e 00 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2eed] # 3fd8 <_ITM_registerTMCloneTable@Base>

10eb: 48 85 c0 test rax,rax

10ee: 74 08 je 10f8 <_start+0x98>

10f0: ff e0 jmp rax

10f2: 66 0f 1f 44 00 00 nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

10f8: c3 ret

10f9: 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

1100: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1104: 80 3d 0d 2f 00 00 00 cmp BYTE PTR [rip+0x2f0d],0x0 # 4018 <__TMC_END__>

110b: 75 33 jne 1140 <_start+0xe0>

110d: 55 push rbp

110e: 48 83 3d ca 2e 00 00 cmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x2eca],0x0 # 3fe0 <__cxa_finalize@GLIBC_2.2.5>

1115: 00

1116: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

1119: 74 0d je 1128 <_start+0xc8>

111b: 48 8b 3d ee 2e 00 00 mov rdi,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2eee] # 4010 <__dso_handle>

1122: ff 15 b8 2e 00 00 call QWORD PTR [rip+0x2eb8] # 3fe0 <__cxa_finalize@GLIBC_2.2.5>

1128: e8 63 ff ff ff call 1090 <_start+0x30>

112d: c6 05 e4 2e 00 00 01 mov BYTE PTR [rip+0x2ee4],0x1 # 4018 <__TMC_END__>

1134: 5d pop rbp

1135: c3 ret

1136: 66 2e 0f 1f 84 00 00 cs nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

113d: 00 00 00

1140: c3 ret

1141: 66 66 2e 0f 1f 84 00 data16 cs nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

1148: 00 00 00 00

114c: 0f 1f 40 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

1150: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1154: e9 67 ff ff ff jmp 10c0 <_start+0x60>

Disassembly of section .fini:

000000000000115c <_fini>:

115c: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1160: 48 83 ec 08 sub rsp,0x8

1164: 48 83 c4 08 add rsp,0x8

1168: c3 ret